High-Protein Diets May Lead to Atherosclerosis

/And - at least according to this paper - one amino acid is to blame.

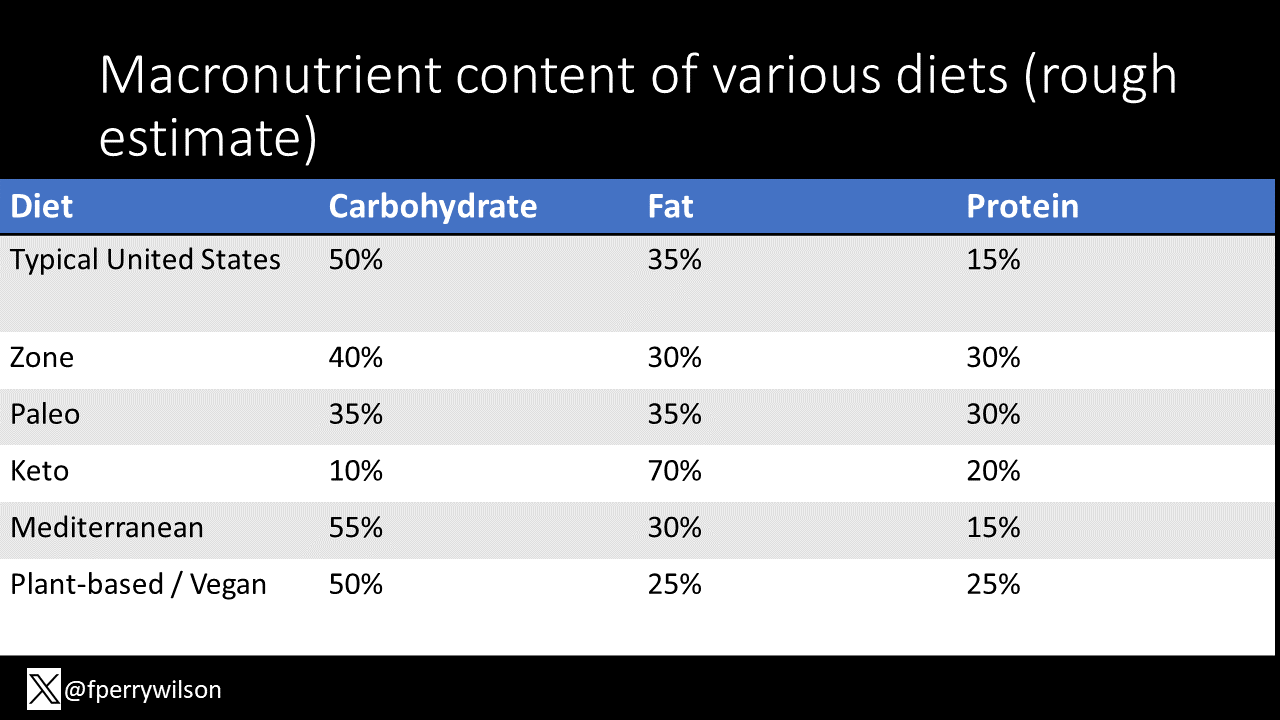

Fat, carbohydrate, protein – the three macronutrients that give us the energy we need to live. Macros are a really convenient way to define the major thrust of the diet wars of the last 40 years. From the late 80s low-fat craze – “fat makes you fat”, to the 90s and aughts shift away from carbohydrates in general and sugar in particular, we arrive now to what seems like a fascination with protein.

High-protein diets like the paleo and Zone diets are gaining in popularity. And though the increasingly popular keto diet is really anti-carb more than pro-protein, any diet that limits one macro will inherently increase the concentrations of the others.

It sort of makes some sense that high-protein diets would be good for you. Good stuff inside your body – muscles and stuff – is made of protein and you are what you eat right? But the data doesn’t necessarily support the contention that high-protein is really that healthy.

Animal studies fairly consistently show that higher protein diets are associated with more atherosclerosis. And some, but by no means all, epidemiologic studies in humans also show a link between protein intake and heart disease.

So are we in trouble? Is there no good macronutrient?

Well – a new paper suggests that some of the observed problems with protein might boil down to just one amino acid – leucine. It’s time to dig in.

We’re talking about this study, appearing in Nature Metabolism from Xiangyu Zhang and colleagues from the University of Pittsburgh.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

To understand the study, you have to understand their central hypothesis. And that is that the ingestion of protein leads to an increase in amino acid in the blood, and somehow one or more of those amino acids stimulate monocytes – inflammatory cells – to activate. The inflammation causes atherosclerosis and, eventually cardiovascular disease. Let’s walk through how they test this paradigm out.

The centerpiece of the paper is two highly controlled, although very brief, human studies. After a 12-hour fast, 14 individuals drank either a low protein shake or a high-protein shake. Later on they would do the opposite, so they served as their own controls. The shakes were matched in terms of calories, and after they drank it, their blood was sampled over the next few hours.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

A parallel experiment had a similar design, except here the individuals ate a solid meal with differing protein content more in the normal ranges of human diets – 15% versus 22% protein intake.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

OK let’s start simple – did ingesting protein increase the amount of amino acids in the blood? Well, of course it did. Compare to lower protein meals, higher protein meals lead to more amino acids. I guess this proves at least that digestion works.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

Much more interesting is their analysis of monocyte activation. They have several biochemical readouts here – I’m showing you S6 phosphorylation but all the results are similar – roughly 20% higher activation in the high-protein state. Similar results were seen in the less extreme solid food study, but, well, less extreme.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

This is a good proof of concept and supports the central hypothesis. Now the researchers had to find which amino acid or acids could be the culprit. They reasoned that whatever the culprit amino acid is, it must be elevated relative to controls in BOTH experiments, which narrowed it down to these 7.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

The usual suspects rounded up, they exposed monocytes in cell culture to them. Now – the dose here is clearly supraphysiologic. These monocytes are positively being flooded with amino acids, but the experiment was successful in showing which ones stimulated them most. Top of the list? Leucine.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

I guess we should do a leucine aside. Leucine is one of three branched-chain amino acids and is an essential amino acid – we have no biologic pathways to create it – we can only take it in from the protein we eat.

And lots of foods we eat contain leucine. I mean, any food that is high in protein is going to be somewhat high in leucine – I put some examples here - but I will note that, in general, animal proteins are higher in leucine than plant-based proteins. Remember that fact we’ll come back to it later.

OK back to the study. Crazy doses of leucine stimulate monocytes. What about normal doses? The researchers exposed monocytes to the same concentration of leucine interest that were observed from the blood of participants in the feeding studies – so like a reasonable range of concentrations.

This is a western blot but darker top bars means more activation of monocytes – and that’s what you see, in a dose-dependent fashion.

Source: Zhang et al. Nature Metabolism. 2024

There’s a lot more to this paper – I’m not even touching the moue studies which showed similar findings. What I will say is, taken together, this paper paints an intriguing explanation for what I might call the “protein paradox” – if high-fat diets are bad, and high-carb diets are bad, and high-protein diets are bad, are we supposed to just not eat?

That’s half a joke because of course maybe the answer is that a balanced diet is optimal. But actually I want to use that joke to highlight the fact that all this talk about macros ignores the fact that these studies control total calorie intake completely- they match calories and vary the percent of calories from each macro. That might not be how the real world works. If a certain diet is high in protein, but leads you to consume less calories than you otherwise would have – well the benefit of taking in less calories may easily outweigh any hypothetical harm from the extra leucine.

But if you’re still worried about protein, remember where the leucine lives – predominantly animal proteins. That means if you want to continue to favor protein as your macro of interest, the best place to get it may be from plant sources. That means we may be able to give a few more points in the column of the leader of the diet wars, 2020s edition – the plant-based diet.

Bon appetit.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.