Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Football-Players

/An autopsy study reveals that 99% of the brains of NFL players had evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Will this condition be the end of football? For the video version, click here.

Read MoreContrast Nephropathy: The Biggest Cause of Acute Kidney Injury that Might Not Exist

/A study appearing in Annals of Emergency Medicine suggests that iodinated contrast material, long-implicated in the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury, may have no role to play at all. For the video version, click here.

Read MoreHuge Chinese Study Suggests 20% of Heart Disease due to Low Fruit Consumption

/A 柚子 a day keeps the doctor away? Appearing in the New England Journal this week is a juicy study that suggests that consuming fresh fruit once daily can substantially lower your risk of cardiovascular disease. In fact, the study suggests that 16% of cardiovascular death can be attributed to low fruit consumption. For those of you keeping score, that's pretty similar to the 17% of cardiovascular deaths that could be prevented if older people stopped smoking.

For the video version of this post, click here.

What we're dealing with here is a prospective, observational cohort of over 500,000 Chinese adults without a history of cardiovascular disease. At baseline, they were asked how often they consumed a variety of foods, and gave a qualitative answer. Most of the analyses compare people eating fruit "daily" to those who ate fruit "rarely or never".

Those fruit-eaters were substantially different from the non-fruit eaters, but not, perhaps, in the way you might expect. For example, waist circumference and BMI were higher in the fruit-eaters and fruit-eaters were much more likely to live in urban rather than rural areas. Fruit-eaters also ate more meat, all suggesting that, in China at least, eating more fruit might be a marker of better nutrition overall. Reporting the cardiovascular effects of more frequent eating of other foods would reveal whether this is the case, but that data was not shown.

More in line with our Western expectations, fruit-eaters had a substantially higher income, more education, and were less likely to smoke or drink alcohol.

After more than 3 million person-years of follow-up, there were 5,173 cardiovascular deaths. If you followed a group of 1000 fruit-eaters for a year, you'd expect less than 1 cardiovascular death. Following a similar-sized group of never-fruit eaters, you'd expect 3.7 deaths.

These observations withstood adjustment for socioeconomic factors, smoking, physical activity, BMI and consumption of other types of food, though unmeasured confounding always plays a role in dietary studies.

Why does it work? We don't know. Though the frequent fruit-eaters had lower blood pressure and lower blood sugar, these factors did not explain the protective effects of the fruit.

Indeed, maybe it's not something in fruit that is beneficial at all, but something that isn't. Like sodium. Fresh fruit isn't salty and salt-intake was not captured in this study. Missing data like that makes it hard to trust that the observed relationship is truly causal.

Still, there isn't much harm in advising patients to eat fresh fruit more regularly, which is I suppose, what makes studies like these so appealing.

Rosacea linked to Parkinson disease: Is this remotely plausible?

/The title of the manuscript is:

Titles like that remind me of the time I was in South Africa and ran into an evangelical Christian basketball team. I know what both of those things are, but I’d never thought of putting them together. Nevertheless that’s the study that appears in JAMA Neurology. So are we playing epidemiology roulette, or is this a real finding? Should your patients with rosacea be concerned?

For the video version of this post, click here.

First things first, this is a study out of Denmark, a country with a nationalized and central health care system. Researchers examined… well… everyone in the country over age 18 from 1997 to 2011, so over 5.5 million people. They identified around 68,000 individuals with rosacea based upon either administrative codes or having received two prescriptions of topical metronidazole. They identified individuals with Parkinson disease based, again, on administrative codes. A sensitivity analysis looked at all those people who got medications associated with Parkinson disease, like levodopa.

Overall, those with rosacea were twice as likely to subsequently receive a diagnosis of Parkinson disease. After adjustment for a fair amount of covariates, the risk was lessened but still significant. Of course, that’s a relative risk. In absolute terms we’re talking about rosacea increasing the risk of Parkinson Disease from 3.5 cases per 10,000 person-years to 7.5 cases per 10,000 person years.

So… why? Well, the authors note that rosacea is associated with upregulation of a group of proteins called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which have a role in tissue breakdown and repair. There is also a mouse model of Parkinson disease that shows upregulation of MMPs. A prior observational study of 70 patients with Parkinson disease showed a higher than expected rate of rosacea. But basically, that’s it. This is the first large, epidemiologic study to even examine the association between these two conditions.

Now I could mention that administrative codes are poor at capturing conditions like this, that people with rosacea may have more contact with the healthcare system and thus be more likely to receive a diagnosis of Parkinson disease, and that the study lacked a negative control condition – say Alzheimer’s dementia – to lend support to the biologic plausibility argument. But I don’t want to be cynical. This paper clearly represents the first foray into an area that probably warrants a deeper look.

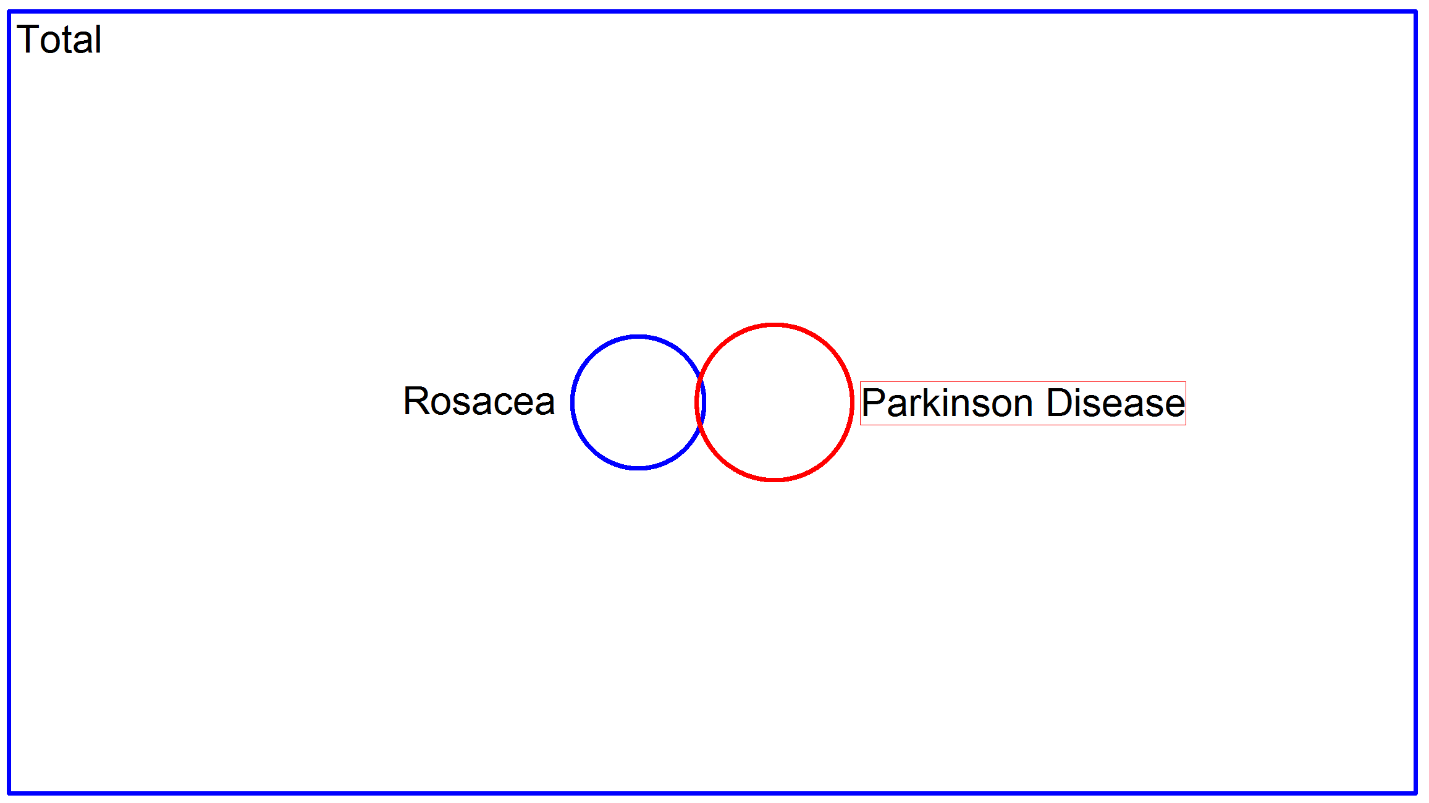

The important thing to remember though, is that even if this is a real finding, the impact for your patients with rosacea is quite minimal. I took the liberty of making a proportional Venn diagram here which I think is illustrative:

The big blue rectangle represents the total population of Denmark, and the circles represent the two disease conditions. There is some overlap between rosacea and Parkinson disease, but I think it should be very clear that most patients with rosacea needn’t worry. It is for this reason that I take issue with this statement:

Pregnancy, Multiple Sclerosis, and Vitamin D: The Latest Hype

/A study appearing in JAMA neurology links better Vitamin D level in pregnant women to a lower risk of multiple sclerosis in their offspring. There are some really impressive features of this study, but there are some equally impressive logical leaps that seem to defy the force of epidemiologic gravity. Let's give the study some sunlight.

For the video version of this post, click here.

The study was run out of Finland, which is a country that figured it might be a good idea to keep track of the health of its citizens. In fact, since 1983, nearly every pregnant woman in Finland has been registered, and a blood sample sent to a deep freezer in a national biobank. The researchers identified 193 individuals with MS, and went back into that biobank to measure their moms' vitamin D levels during pregnancy. They did the same thing with 326 controls who were matched on their date of birth, mother's age, and region of Finland.

This is from the first line of their discussion:

Wow. 90%. That sounds scary. And the news outlets seem to think it is scary too. But that impressive result hides a lot of statistical skullduggery.

Here's the thing, Vitamin D level is what we call a continuous variable. Your level can be 5, 10, 17, 42, whatever – any number within a typical range. When you study a continuous variable, you have to make some decisions. Should you chop up the variable into categories that others have defined (like deficient, insufficient, normal), or should you chop it up into even-sized groups? Or should you not chop it up at all?

As a general rule, you have the most power to see an effect when you don't chop at all. Breaking a continuous variable into groups loses information.

When the Vitamin D level was treated as the continuous variable it is, there was no significant relationship between Vitamin D level in mom and MS in the child. When the researchers chopped it into 5 groups, no group showed a significantly higher risk of MS compared to the group with the highest level. Only when they chopped the data into 3 groups did they find that mom's who were vitamin D deficient had 1.9 times the risk of those that were insufficient. That's the 90% figure, but the confidence interval ran from 20% to 300%.

And did I mention there was no accounting for mothers BMI, smoking, activity level, genetic factors, sun exposure or income in any of these models? Despite that, the paper's conclusion states :

That statement should go right on the jump to conclusions mat.

Look, I'm not hating on Vitamin D. I actually think it's good for you. But research that adds more to the hype and less to the knowledge is most definitely not.

Antidepressants, pregnancy, and autism: the real story

/For the video version of this post, click here.

If you're a researcher trying to grab some headlines, pick any two of the following concepts and do a study that links them: depression, autism, pregnancy, Mediterranean diet, coffee-drinking, or vaccines. While I have yet to see a study tying all of the big 6 together, waves were made when a study appearing in JAMA pediatrics linked antidepressant use during pregnancy to autism in children.

To say the study, which trumpets an 87% increased risk of autism associated with antidepressant use, made a splash would be an understatement:

The Huffington post wrote:

The Daily telegraph, rounding up, said:

Newsweek:

But if you're like me you want the details. And trust me, those details do not make a compelling case to go flushing all your fluoxetine if you catch my drift.

Researchers used administrative data from Quebec, Canada to identify around 145,000 Singleton births between 1998 and 2009. In around 3% of the births, the moms had been taking anti-depressants during at least a bit of the pregnancy. Of those kids, just over 1000 would be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in the first 6 years of life. But if you break it down by whether or not their mothers took antidepressants, you find that the rate of diagnosis was 1% in the antidepressant group compared to 0.7% in the non-antidepressant group. This unadjusted difference was just under the threshold of statistical significance by my calculation, at a p-value of 0.04.

These numbers aren't particularly overwhelming. How do the researchers get to that 87% increased risk? Well, they focus on those kids who were only exposed in the second and third trimester, where the rate of autism climbs up to 1.2%. It's not clear to me that this analysis was pre-specified. In fact, a prior study found that the risk of autism increases only when antidepressants are taken in the first trimester:

And I should point out that, again by my math, the 1.2% rate seen in those exposed during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters is not statistically different from the 1% rate seen in kids exposed in the first trimester. So focusing on the 2nd and 3rd trimester feels a bit like cherry picking.

And, as others have pointed out, that 87% is a relative increase in risk. The absolute change in risk remains quite small. If we believe the relationship as advertised, you'd need to treat about 200 women with antidepressants before you saw one extra case of autism.

But I'm not sure we should believe the relationship as advertised. Multiple factors may lead to antidepressant use and an increased risk of autism. Genetic factors, for example, were not controlled for, and some studies suggest that genes involved in depression may also be associated with autism. Other factors that weren't controlled for: smoking, BMI, paternal age, access to doctors. That last one is a biggie, in fact. Women who are taking any chronic medication likely have more interaction with the health care system. It seems fairly clear that your chances of getting an autism diagnosis increase with the more doctors you see. In fact, in a subanalysis which only looked at autism diagnoses that were confirmed by a neuropsychologist, the association with antidepressant use was no longer significant.

But there's a bigger issue, folks – when you take care of a pregnant woman, you have two patients. Trumpeting an 87% increased risk of autism based on un-compelling data will lead women to stop taking their antidepressants during pregnancy. And that may mean these women don't take as good care of themselves or their baby. In other words, more harm than good.

Could antidepressants increase the risk of autism? It's not impossible. But this study doesn't show us that. And because of the highly charged subject matter, responsible scientists, journalists, and physicians should be very clear. Women taking anti-depressants during pregnancy, do not stop until, at the very least, you have had a long discussion about the risks with your doctor.