Shocking: Black children are 80% less likely to get opioids for appendicitis

/For the video version of this post, click here. I usually don't get concerned about the results of observational studies. I can often convince myself that there is some confounder or issue of study design that makes the results less dramatic than they seem. This week, I saw an observational study that genuinely worried me.

Its long been noted that black patients get treated differently in the ER. Specifically, black patients get less opioid pain medication, and less aggressive interventions. Much of this relationship was explained in the past by something called spectrum bias. The idea is that if a population of individuals uses the ER for less severe illnesses, the treatment they receive will naturally be less intense - no bias, no racism, just statistics.

That's what makes this study, appearing in JAMA pediatrics, so interesting. Researchers from Childrens national hospital in Washington DC analyzed a nationwide sample of children treated for appendicitis in the nations ERs. The elegance here is that pain associated with appendicitis should be similar across populations. Indeed, the triage pain scores were no different between black and non-black kids in this study.

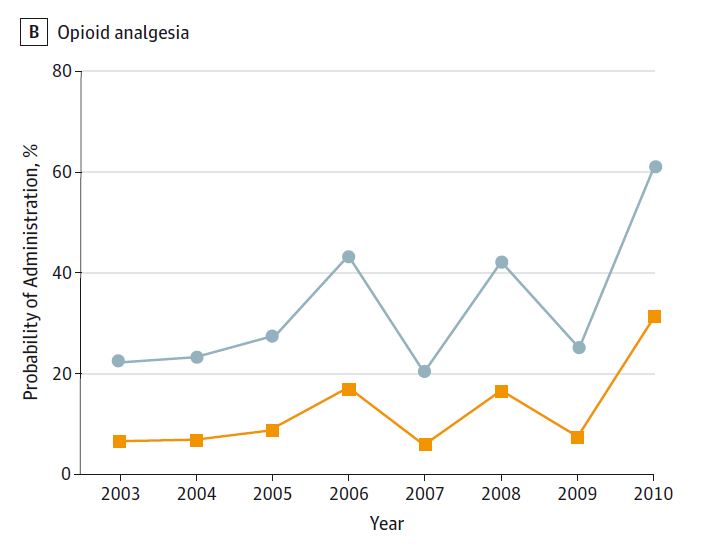

Here's the bottom line: there were around 1 million appendicitis cases in children between 2003 and 2010. While both black and non-black children got analgesia around 55% of the time, non-black children got opioid analgesia 43% of the time, while black children got opioid analgesia just 20% of the time. This relationship persisted after adjustment for pain score, insurance status, age and sex. In fact, after considering those factors, black children were about 80% less likely to receive opioid analgesia than non-black children.

If true, this is simply unacceptable. It speaks to either an overt, or implicit bias in the medical system, whereby children in pain are treated not according to their symptoms, but to the color of their skin. But this wasnt a randomized trial - how could it be? Should we believe the results?

There are a couple of signals in the data to note. First, the data presented has significant variability. For instance, according to the study the rate of opioid analgesia usage was 25% in 2004, but 55% in 2005.

Such year-to-year fluctuation is hard to believe. If the data quality isnt up to snuff, then the results we see here shouldnt be completely trusted.

We should also acknowledge the fact that when physicians are unsure of a diagnosis of appendicitis in a child, they will often withhold opioids to see how the case develops. This practice could systematically differ in hospitals that cater to different populations, and drive some of the relationship seen here.

Despite these facts, these numbers are dramatic. Were not talking about a couple of percentage points that can be explained away by subtle issues of study design or data acquisition. I join my voice with the authors who state that dedicated studies of disparities in this area are urgently needed. I hope you do too.